Ann Herbert was the patron of poem 26, the only poem known to have been addressed to her. It is a poem of comfort following the death of her husband.

Her lineage and family

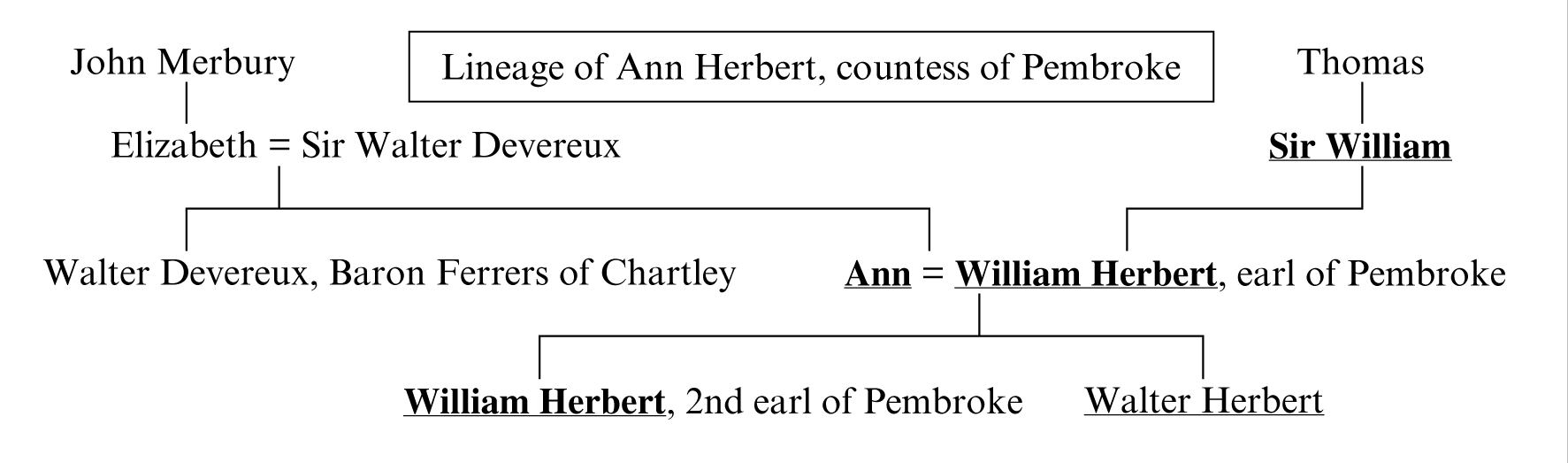

Ann was the daughter of Sir Walter Devereux of Weobley, Herefordshire (DNB Online s.n. Devereux, Walter). Hers was an influential family in that region. In 1449 she married William Herbert of Raglan (WG1 ‘Godwin’ 8), a member of the Welsh gentry who lived at Raglan castle in the lordship of Usk (now in Monmouthshire). This marriage was a significant advance in William Herbert’s career: it ensured for him a network of allies and supporters in Herefordshire. All through the 1450s and 1460s there was close cooperation between the Devereux and Herbert families, both being tenants and supporters of Richard, duke of York, and afterwards of his son Edward IV. Ann’s father died in 1459, but the close relations between the two families endured. Ann’s brother, Walter Devereux, was firmly associated with William Herbert in his efforts to win the loyalty of south Wales for the king. When Herbert was made earl of Pembroke on 8 September 1468 (Thomas 1994: 40), Ann Herbert became countess of Pembroke (in the genealogical table below those named by Guto in his poem to Ann are shown in bold print and the names of his patrons are underlined).

Lineage of Ann Herbert, countess of Pembroke

Her sons

Ann Herbert and her husband had both sons and daughters. The eldest son, William, second earl of Pembroke, was born around 1455 (Thomas 1994: 73n1). The second son was Walter Herbert. Both men would later patronize Guto’r Glyn, but when William Herbert’s life was cut brutally short in 1469, they were both still underage. Another boy brought up under the care of Ann Herbert was Henry Tudor, son of Edmund Tudor and Margaret Beaufort. When William Herbert seized Pembroke castle in the name of Edward IV in 1461, he took possession of the young boy and brought him to Raglan. In 1462 the king granted him in wardship to Herbert for the sum of £1000 (ibid. 28). After Henry became king in 1485 he remembered his foster-mother and treated her with deference (Griffiths and Thomas 1985: 58–9).

There is a well-known contemporary image of William Herbert and his wife kneeling before Edward IV, in a manuscript made for presentation to the king. It is reproduced in Lord (2003: 260).

The troubles after her husband’s death

William Herbert was executed on 27 July 1469, following his defeat at the battle of Edgecote (Banbury). He had been at the zenith of his power and influence. This must have been a dreadful blow to Ann Herbert and her family, and the safety of her young sons must have been a great worry to her as she watched Herbert’s enemies contending for control of the kingdom. On 23 November 1469 Ann Herbert, countess of Pembroke, received into her care all her husband’s property for as long as the second earl should be underage, a grant confirmed in May 1470 (Thomas 1994: 97). In his will, made 16 July 1469, Herbert had entrusted to her ‘the chief rule in performing my will and to be one of my executors’ (ibid. 107–8). Thomas (ibid. 97) draws attention to documentary evidence that Ann Herbert was indeed looking after her son’s estates in 1470. However, it does appear that she returned at least for a time to her family home in Weobley, where her brother could protect her (DNB Online s.n. Devereux, Walter). By May 1471, after the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury, Ann and her sons could feel more secure. Their chief enemy, the earl of Warwick, was killed at Barnet, and by now Edward IV’s position was assured. It is most likely to this period that poem 26 belongs, a period of new hope after the disasters of 1469–71. We do not know whether Ann could understand Welsh, but certainly by 1471 she had spent more than twenty years at Raglan, a court where Welsh was often spoken and which often welcomed Welsh poets. She would, therefore, be aware of the role played by the poets and the importance of the act of patronizing them, even if she could not herself understand every word of the poems.

In the codicil to his will which William Herbert made on the morning of his execution, he refers to Ann’s promise to remain chaste after he died. It appears that she kept her promise, for Guto in 26.45 refers to her wearing the outward symbols of that undertaking, the ring and mantle worn by widows who had sworn not to remarry.

Under the terms of William Herbert’s will the lordship of Chepstow was placed in Ann’s possession until her death (Thomas 1994: 107; Griffiths 2008: 248; Robinson 2008: 310). She died around 18 August 1486 (Robinson 2008: 329n8).

Bibliography

Griffiths, R.A. (2008), ‘Lordship and Society in the Fifteenth Century’, R.A. Griffiths et al. (eds.), The Gwent County History, 2: The Age of the Marcher Lords, c.1070–1536 (Cardiff), 241–79

Griffiths, R.A. and Thomas, R.S. (1985), The Making of the Tudor Dynasty (Stroud)

Lord, P. (2003), The Visual Culture of Wales: Medieval Vision (Cardiff)

Robinson, W.R.B. (2008), ‘The Early Tudors’, R.A. Griffiths et al. (eds.), The Gwent County History, 2: The Age of the Marcher Lords, c.1070–1536 (Cardiff), 309–36

Thomas, D.H. (1994), The Herberts of Raglan and the Battle of Edgecote 1469 (Enfield)