Two of Guto’s poems for Edward ap Dafydd, the head of the Bryncunallt family in Chirk, have survived:

- ‘In praise of the sons of Edward ap Dafydd of Bryncunallt’ (103)

- ‘Elegy for Edward ap Dafydd of Bryncunallt’ (104)

There are no other poems for Edward. Guto sang an elegy for Edward’s eldest son Robert Trefor (poem 105), and later in his career he claims that he received patronage from Siôn Trefor, Edward’s second son, but the poems have not survived. Guto’s surviving poetry to the family of Bryncunallt can be dated between the early 1440s and 1452. Further on Edward’s sons see below.

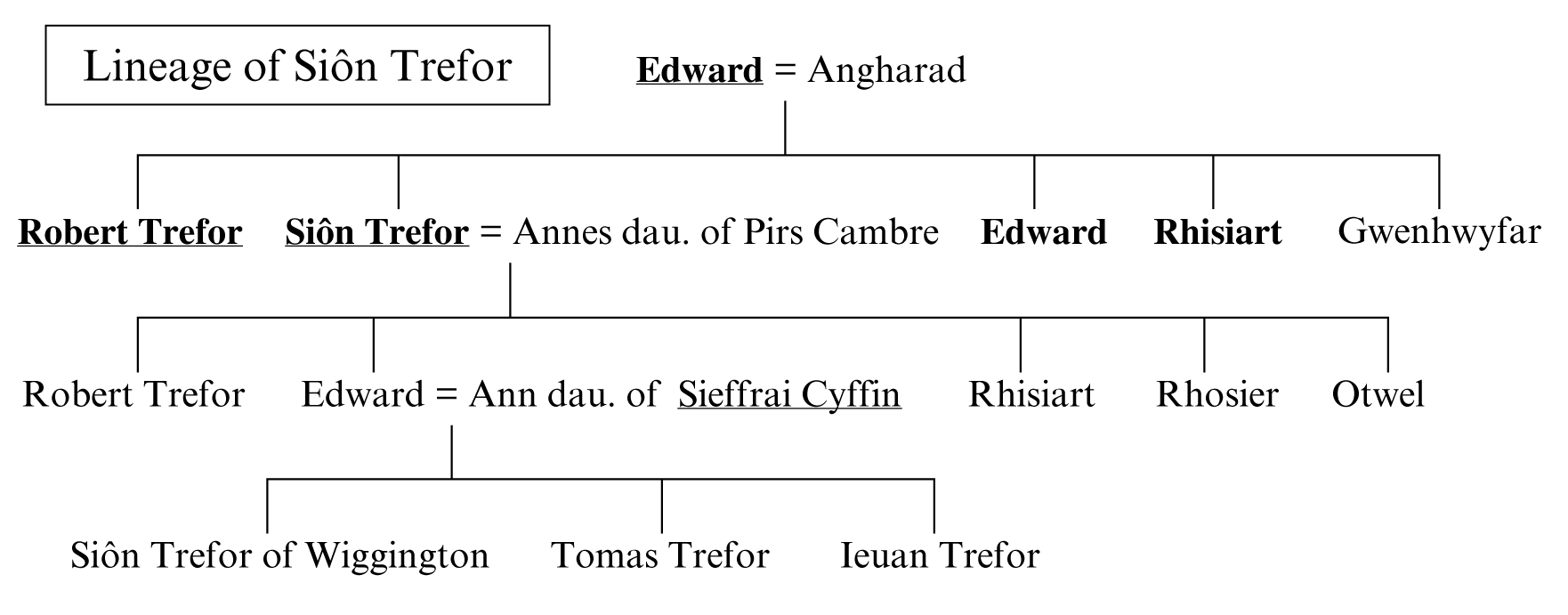

Lineage

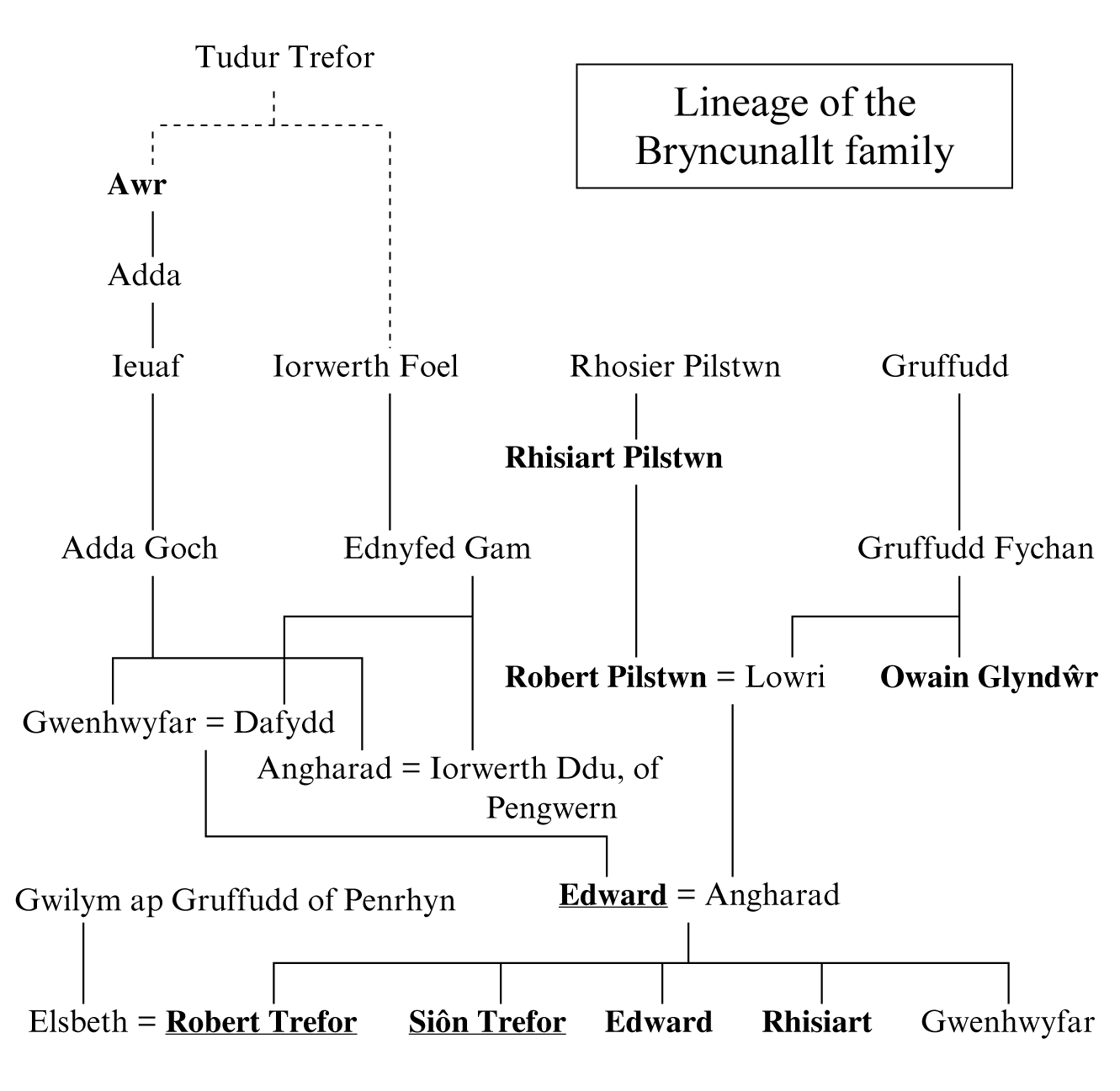

The lineage below is based on information gleaned from WG1 ‘Tudur Trefor’ 13, 14, ‘Marchudd’ 6, ‘Bleddyn ap Cynfyn’ 5, WG2 ‘Tudur Trefor’ 14C1; HPF iv: 16. Those named in poems 103–5 (or alluded to in the case of Owain Glyndŵr) are given in bold, and the patrons are underlined.

Lineage of the Bryncunallt family

The two brothers Iorwerth Ddu and Dafydd, sons of Ednyfed Gam, were married to two sisters, Angharad and Gwenhwyfar, daughters of Adda Goch ab Ieuaf ab Adda ab Awr, bringing together two important branches of the Tudur Trefor clan. This descent from Awr is frequently mentioned by Guto in his poems to the family, possibly because of the assumed link between Awr and Trefor near Llangollen, one of the family’s principal seats in Nanheudwy (see 103.22n). Siôn Trefor, of Trefor, the bishop of St Asaph in 1346–57, was the son of Llywelyn, a brother of Adda Goch; the second Siôn Trefor who became bishop of St Asaph in 1394–1410, was the son of Angharad and Iorwerth Ddu. (See Jones 1965: 38; Jones 1968: 36–46; for Iolo Goch’s poetry to one or both Siôn Trefors, see IGP notes to poem XVI.) This later Bishop Siôn Trefor was therefore the brother of Myfanwy to whom Hywel ab Einion Lygliw composed an ode of praise and love, and who became the wife of Goronwy Fychan of Penmynydd (see below).

By marrying Angharad, daughter of Robert Puleston, Edward ap Dafydd ensured a close connection with two other very important families in the area: the upwardly mobile Pulestons, with their main home in Emral near Wrexham (see further Siôn ap Madog Puleston of Hafod-y-wern and Rhosier ap Siôn Puleston of Emral), and the family of Owain Glyndŵr, a traditional Welsh family that could trace its descent back to the princes of Powys and Gwynedd. Guto is very careful to remind his audience of these important connections (e.g. 103.23–6).

It is quite possible that Edward himself had not been a patron of poetry, and that it was his wife, Angharad daughter of Robert Puleston, who first introduced poets to Bryncunallt. At least two of his sons, Robert Trefor and Siôn Trefor, became patrons, and poems to them by Guto’r Glyn and Gutun Owain have survived (see below).

His dates

We can be fairly confident of the date Edward died. In Pen 26, 97–8, there is a stray folio containing contemporary notes written by various hands dated between 1439 and 1461 on matters relating to the Oswestry area. Many of the entries refer specifically to members of the Trefor family of Bryncunallt, which may suggest that it was members of that family who were responsible for recording them. One entry states that Edward ap Dafydd died on 25 April 1445: Obitus Edwardi ap Dafydd in festo Marci evengeliste anno domini MCCCXLV (see Phillips 1970–2: 76). The earliest reference to him is in a deed dated 11 March 1390 (Ba (M) 1629), and we can assume that he would have been born at least 15–20 years previously. He would have been in his seventies at least in the 1440s when Guto Guto sang to him and his four sons (poem 103), and although Edward is described as the family’s [p]enadur ‘chieftain’ (103.59), it is obvious that it was his eldest son, Robert Trefor, who was the effective leader of the family by then. In his elegy (poem 104), despite conveying the region’s very great sorrow at losing such an authoritative and learned leader, the message is a positive one, focussing on the the future which is secure in his sons’ hands. We can assume that his death was not entirely unexpected.

Land

Dafydd, Edward’s father, was the son of Ednyfed Gam of Pengwern, Llangollen, and the head of one of the most important families in Nanheudwy. His family grew in prosperity and authority during the fourteenth century by increasing its landholdings in the region: ‘By the fourteenth century the family of Ednyfed Gam, described in the genealogies as “of llys Pengwern in Nanheudwy” already stood out as substantial members of the lordship’s free community’ (Smith 1987: 177). By the end of the century they were notable landowners in Nanheudwy, especially in Chirk, Trefor and Llangollen.

The extent of the lands of Chirkland carried out by Robert Eggerley in 1391/2 shows that Ednyfed Gam’s lands were shared amongst his heirs. Iorwerth Ddu, the eldest son, inherited the family’s ancestral home in Pengwern, Llangollen, and he also held, with his brother Ieuan, four gafaelion and one castellum (a measure of land) in the township of Gwernosbynt (Jones 1933: 58–9). The extent further shows that Dafydd ab Ednyfed Gam owned one and a half gafaelion in the township of Bryncunallt and also a mill named Grostith in the same township (ibid. 9). Dafydd also held Plas Teg, Hope, where his great-grandson, Robert Trefor ap Siôn Trefor, would later reside (Glenn 1925: 23).

Learning and career

We learn from Guto’s poetry that Edward was a very learned man, and the specific reference to his expertise in the ‘two laws’ (civil and ecclesiastical) as well as in the arts may suggest that he had received an university education, although there is no external evidence to support this (see in particular 104.9–10, 21–32). Edward probably received some of his elementary education at Valle Crucis (the kind of education described in Thomson 1982: 76–80), or possibly at the school which had flourished in Oswestry since the early years of the fifteenth century (Griffiths 1953: 64–6 et passim). We can be sure that there was a strong connection between the Pengwern and Trefor branches of the family and the abbey, as many family members were buried there. Guto testifies that Robert Trefor’s final resting place was within the abbey’s grounds, and it is believed that Edward ap Dafydd was also buried there (see CTC 362, but no source is given).

Guto suggests that Edward ap Dafydd had a role in administering law and order in Chirk (poem 104), but we have no external evidence to support this either. However, the fact that Edward’s name appears in deeds regarding the conveyance of land in the region does suggest his status within society: e.g. he is named in a deed issued in Chirk, 11 March 1390 (Ba (M) 1629); as witness to a deed dated 15 May 1391 at Trefor (Jones 1933: 93) and in a similar deed dated 29 September 1411 at Lower Trefor (LlGC Bettisfield 977); and in another, he is named together with his son Robert regarding the receipt of land in Nanheudwy in 1441 (LlGC Puleston 935). He may also be the magister Edward Trevor who is named in a deed dated 1427 regarding land in Chirk, Lower Chirk and Gwernosbynt (LlGC Chirk Castle 920), although that may have been his son. Like many members of his family, Edward took part in the Glyndŵr rebellion, and along with many of the local landowners he later had to forfeit his land to the lord. By 1407 peace was restored and, following the payment of a twenty pound fine, his lands were restored to him (Carr 1976: 27).

Robert Trefor ab Edward, fl. c.1429–d. 1452

Edward ap Dafydd’s eldest son and heir: see Robert Trefor.

Siôn Trefor ab Edward, fl. c.1440–d. 1493

Siôn Trefor (or Siôn Trefor Senior, to distinguish between him and many other descendants of the same name) was the second son of Edward ap Dafydd, and it was he who became the head of the household at Bryncunallt when his older brother, Robert Trefor, died in 1452. He is named in the three surviving poems by Guto to this family (poems 103–5), and it is quite possible that it was under his patronage that Guto sang his elegy for Robert Trefor (poem 105). Although no poems by Guto to Siôn dating after 1452 have survived, it is possible that he received his patronage throughout his career. Guto testifies on more than one occasion in the 1480s that Siôn Trefor, who lived in Pentrecynfrig by then, was one of his main patrons (see 108.20, 117.56). It is likely that Guto would have composed an elegy in 1483 for Annes, Siôn’s wife, but if so, that poem, as well as the other poems sung at their home, has been lost. Gutun Owain sang to Siôn Trefor and Annes in Pentrecynfrig, and to their sons, as did Lewys Môn, Tudur Aled and Ieuan Teiler. The following poems for them have been preserved:

- an elegy for Annes Trefor of Pentrecynfrig, 1483, by Gutun Owain, GO XXXV;

- an elegy for Siôn Trefor by Gutun Owain, 1493, GO XXXVI;

- a poem for the three Trefor brothers (Otwel, Robert (Rhapat) and Edward) by Gutun Owain, before 1487, GO XXXVII;

- an elegy for Robert Trefor of Hope by Gutun Owain, 1487, GO XXXVIII;

- praise for Edward Trefor Fychan by Lewys Môn, GLM LXXV;

- praise for Edwart Trefor by Tudur Aled, TA LI;

- praise for Rhosier, Rhisiart and Edward, sons of Siôn Trefor, by Ieuan Teiler, after 1487, Pen 127, 257.

The date of Siôn Trefor’s death, 1493, is given in his elegy by Gutun Owain (GO XXXVI.23–30), namely Friday, 6 December 1493, and Gutun notes that he was buried on the following Sunday. The date is confirmed by a contemporary entry in Pen 127, 15: Oed Crist pann vv varw John trevor ap Edwart ap dd 1493 duw gwner (sic) y vied dydd o vis Racvyr ‘Christ’s age when John Trevor ap Edward ap D[afyd]d died was 1493, Friday the sixth day of December.’ Annes, Siôn’s wife, died ten years earlier in 1483 (GO 202). As the lineage below shows, they had five sons, one of whom, Otwel, died young whilst another, Robert Trefor, died in 1487. Four of the sons – Robert, Siôn, Edward and Rhisiart Trefor – are named as burgesses in Oswestry in the second half of the fifteenth century (see Oswestry Archives OB/A12), possibly suggesting that Otwel had died before Robert. When Gutun Owain sang his elegy for Siôn Trefor in 1493, he named three sons – Enwoc Edwart, … / Rroeser a ddwc aur rrossynn, / Rrissiart … ‘Renowned Edward, … / Rhosier who bears a golden rose, / Rhisiart …’ (GO XXXVI.49, 51–2) – and there were also grandchildren (ibid. 53 Y mae ŵyrion i’m eryr ‘My eagle has grandchildren’). As Ieuan Teiler does not name either Otwel or Robert Trefor in his poem, it may have been sung after Robert’s death in 1487. Edward, who is also referred to sometimes as Edward Trefor Fychan, was married to Ann daughter of Sieffrai Cyffin, and one of their sons was Siôn Trefor of Wiggington to whom Huw Llwyd later sang (GHD poems 25, 26).

Lineage

The following lineage is based on information gleaned from WG1 ‘Tudur Trefor’ 14 and WG2 ‘Tudur Trefor’ 14 C2. Those named in poems 103–5 are shown in bold print and the names of patrons are underlined.

According to the genealogies, two of Siôn Trefor’s sons, Rhisiart and Rhosier, were twins. There were also two sisters, Elen and Catrin, who are not named in any of the poems.

His home

When Guto sang to the family between c.1440 and 1452 (poems 103–5), Siôn Trefor was based at Bryncunallt, but by the 1480s it seems that his main home was at Pentrecynfrig (today, Pentrekendrick), a township between Weston Rhyn and St Martin’s, about 2km south of Chirk, in Shropshire. When Gutun Owain sang his elegy for Annes, he referred specifically to the grief of Pentrecynfrig: Trais Duw a ’naeth, – trist yw ’nic, – / Trai canrodd Penntre Kynwrric ‘God’s oppresion caused (sad is my grief) / the waning of a hundred gifts at Pentrecynfrig’ (GO XXXV.5–6). And ten years later, in his elegy for Siôn Trefor himself, although he associated his patron with Lower Chirk, Bryncunallt and Oswestry, it was at Pentrecynfrig that his grief was felt most keenly: Oer galon a wna’r golwg / Yn wylo mal niwl a mwc. / Ni welaf eithyr niwlen / Y’mric Penntref Kynnric henn ‘The cold heart renders my sight, / with tears flowing, like fog and smoke. / I cannot see anything but a covering of mist / above ancient Pentrecynfrig’ (GO XXXVI.31–4).

Learning and career

In his elegy for Edward ap Dafydd, Guto lists the various qualities of the father which were inherited by his sons. Siôn Trefor, he says, inherited his father’s scholarly interests. This is corroborated by the fact that it was Siôn Trefor, in all probability, who was responsible for translating the Life of St Martin (the patron saint of St Martins, near Pentrecynfrig) into Welsh; there is a copy of that translation in Gutun Owain’s hand in LlGC 3026C (see Owen 2003: 351; Jones 1945; also 104.43–4). In his elegy for Siôn, Gutun Owain draws attention to the learning of the athro mawr ‘great teacher’ (GO XXXVI.6 et passim). In time, Siôn would pass on these interests to his son, Robert Trefor of Hope, who was described by Gutun Owain as Kerddwr, ysdorïawr oedd / O’n heniaith a’n brenhinoedd ‘He was a poet and a recounter of tales / from our old language and of our kings’ (GO XXXVIII.29–30).

The name Siôn Trefor appears often in contemporary documents but, if it appears without a patronymic, it is difficult to be confident that the reference is to him rather than to one of his many relations of the same name. On 7 July, 1461, he is named along with five other men who were also Guto’s patrons – Abbot Siôn ap Rhisiart, Dafydd Cyffin, Siôn Hanmer, Siôn ap Madog Puleston and Robert ap Hywel (45.49–51) – as one of the king’s attorneys to receive a commission in Chirkland (CPR 1461–7, 37). On 21 September 1474, he is named receiver of Chirkland and as a witness to a deed regarding the transfer of land to Siôn Edward (LlGC Chirk Castle 1077), and again on 3 February 1488 (but not as receiver this time) (LlGC Chirk Castle 9885).

Edward ab Edward, fl. ?1427–c. ?1475

We can assume that Edward was Edward ap Dafydd’s third son based on the order that the four sons are named in poems 103, 104 and in the genealogies. In the genealogies it is also stated that he married Lady Tiptoft and that they had no children. Guto claims that it was Edward who inherited his father’s physical strength: Ei faint a’i gryfder efô / Mewn Edwart mae’n eu ado ‘his physique and his strength / he leaves behind in Edward’ (104.45–6). I have not found another reference to him in the poetry, but he is named with his brothers Robert, Siôn and Rhisiart Trefor as a burgess in Oswestry in the second half of the fifteenth century (see Oswestry Archives OB/A12). He is possibly the magister Edward Trevor named in a deed dated 1427 regarding land in Chirk, Lower Chirk and Gwernosbynt (LlGC Chirk Castle 920), although that may be a reference to his father.

Rhisiart ap Edward, fl. c.1440–68

Rhisiart was probably the fourth son of Edward ap Dafydd, again based on the order in which the sons are named in Guto’s poems and in the genealogies (see above, Edward ab Edward). Rhisiart is also named as a burgess in Oswestry in the second half of the fifteenth century, along with his brothers Robert, Siôn and Edward (see Oswestry Archives OB/A12). It was Rhisiart, according to Guto, who inherited his father’s appearance: Ac i Risiart, ’yn Groeswen, / Ei liw a’i sut a’i lys wen ‘and to Rhisiart, in the name of the Holy Cross, / his complexion and his appearance and his whitewashed court’ (104.47–8). Based on this couplet, it has been suggested that Rhisiart may also have inherited a court in Whittington (cf. Carr 1976: 49n178 and 104.47n). He was constable of Whittington castle in 1468 (LlGC Chirk Castle F 9878).

Two poems in the manuscripts, ascribed to Rhys Goch Glyndyfrdwy and Gruffudd Nannau, discuss the imprisonment by Rhisiart Trefor of Ithel and Rhys, sons of Ieuan Fychan ab Ieuan. Pen 177, 199 gives the following account: Ithel a Rys meib I. Vychan ap Ieuan a aethant i gastell y Drewen ddvw gwener gwyl Gadwaladr y XIIed dydd or gayaf ac a vvant yno hyd difie kyn awst O.K. 1457 ‘Ithel and Rhys, the sons of Ieuan Fychan ab Ieuan, went to Whittington castle on Friday, the feast day of Cadwaladr, on the twelfth day of winter and remained there until Thursday before August, A.D. 1457’ (i.e. 12 November 1456 –28 July 1457). We cannot be sure of the exact circumstances, but Carr (1976: 39–40; cf. Charles 1966–8: 78) suggests that they may have been imprisoned by the Yorkist supporter Rhisiart Trefor because of their support for Jasper Tudor (their cousin), and the Lancastrian cause. Rhys Goch Glyndyfrdwy asks the moon to look for the missing brothers in the castles of England, and hopes that God will ensure that they return safely from Whittington (for the poem, see LlGC 8497B, 190v–191v, my punctuation):

Ysbied, chwilied yn chwyrn

Gestyll Lloegr, gorffwyll gyrn,

Am frodvr o Dvdvr daid,

Ithel a Rhys benaythiaid

Y sydd yn yr ynys hon,

Yryrod, garcharorion …

Duv a ddwg i’n diddigiaw

Dav vnben o’r Drewen draw

‘Spy, and search swiftly

in the castles of England, whose chimneys cause distraction,

for the brothers descended from Tudur, their grandfather,

the chieftains Ithel and Rhys

who are in this region,

eagles, prisoners …

To appease us, God will bring

the two leaders from Whittington yonder.’

It would be interesting to know what Guto’r Glyn’s thoughts were regarding these circumstances. Were his sympathies with the Pengwern family? Is that why there aren’t any poems to the patrons in Bryncunallt from the middle years of his career? (See further Ieuan Fychan ab Ieuan of Pengwern; the background note to poem 106, 48.38n and further on the poems of Rhys Goch Glyndyfrdwy and Gruffudd Nannau, see Bowen 1953–4: 119–20.)

Bibliography

Bowen, D.J. (1953–4), ‘Carcharu Ithel a Rhys ab Ieuan Fychan’, NLWJ viii: 119–20

Carr, A.D. (1976), ‘The Mostyn Family and Estate, 1200–1642’ (Ph.D. Cymru [Bangor])

Charles, R.A. (1966–7), ‘Teulu Mostyn fel noddwyr y beirdd’, LlCy 9: 74–110

Glenn, T.A. (1925), History of the Family of Mostyn of Mostyn (London)

Griffiths, G.M. (1953), ‘Educational Activity in the Diocese of St. Asaph, 1500–1650’, Journal of the Historical Society of the Church in Wales, III: 64–77

Jones, B. (1965) (ed.), John Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300–1541: XI The Welsh Dioceses (London)

Jones, E.J. (gol.) (1945), Buchedd Sant Martin (Caerdydd)

Jones, E.J. (1968), ‘Bishop John Trevor (II) of St. Asaph’, Journal of the Historical Society of the Church in Wales, XVIII: 36–46

Jones, G.P. (1933), The Extent of Chirkland (1391–1393) (London)

Owen, M.E. (2003), ‘Prologemena i Astudiaeth Lawn o Lsgr. NLW 3026, Mostyn 88 a’i Harwyddocâd’, I. Daniel, M. Haycock, D. Johnston a J. Rowland (goln.), Cyfoeth y Testun: Ysgrifau ar Lenyddiaeth Gymraeg yr Oesoedd Canol (Caerdydd)

Pratt, D. (1977), ‘A Holt Petition, c. 1429’, TDHS 26: 153–5

Phillips, J.R.S. (1970–2), ‘When did Owain Glyn Dŵr Die?’, B xxiv: 59–77

Smith, Ll.B. (1987), ‘The Grammar and Commonplace Books of John Edwards of Chirk’, B xxxiv: 174–84

Smith, Ll.O.W. (1970), ‘The Lordships of Chirk and Oswestry 1282–1415’ (Ph.D. University of London)

Thomson, D. (1982), ‘Cistercians and Schools in Late Medieval Wales’, CMCS 3: 76–80